Myth and Truth

A man who disbelieved the Christian story as fact but continually fed on it as myth would, perhaps, be more spiritually alive than one who assented and did not think much about it.” So claimed C. S. Lewis in his 1944 essay “Myth Became Fact.” Lewis insisted that myth lies at the heart of the faith—even if it embarrasses those moderns who would cover over the mythic imagery of Scripture with the whitewash of literalism, replacing lively stories with morals, principles, and ideas. The similarities between the Christian faith and the myths of the pagans need not occasion unease, Lewis argued; rather, they manifest a “mythical radiance” that should be preserved within our theology.

…

Jordan Peterson is an especially vivid example of one who feeds upon the Christian story as myth, while not believing it as fact. He is far from alone, and though We Who Wrestle with God is not a true Christian reading of Holy Scripture, it represents an encouraging trend of serious thinkers recognizing the vital cultural significance of the Bible. This trend may be a much-needed beachhead for the evangelization of righteous pagans—and a spur to Christians to return to a spiritual reading of Holy Scripture. In myth, as Lewis recognized, meaning is encountered neither as abstract nor as bound to the particular, but as reality. And in the Incarnation, myth and fact are joined.

Alastair Roberts, Jordan Peterson’s “God”.

My attitude toward Jordan Peterson is vexed. I pray for him as a very important Christian-adjacent “influencer” — that he will lead his (mostly young, or so I hear) followers to good places and that he himself will embrace the Orthodox Christian faith to which he is is multiple ways very close. On the other hand, I don’t have time for his logorrhea and circumlocution.

Ritual

The genius of ritual is that it allows us not to articulate our feelings. It allows us to express our faith through an act.

Andrew Sullivan via Peter Savodnik

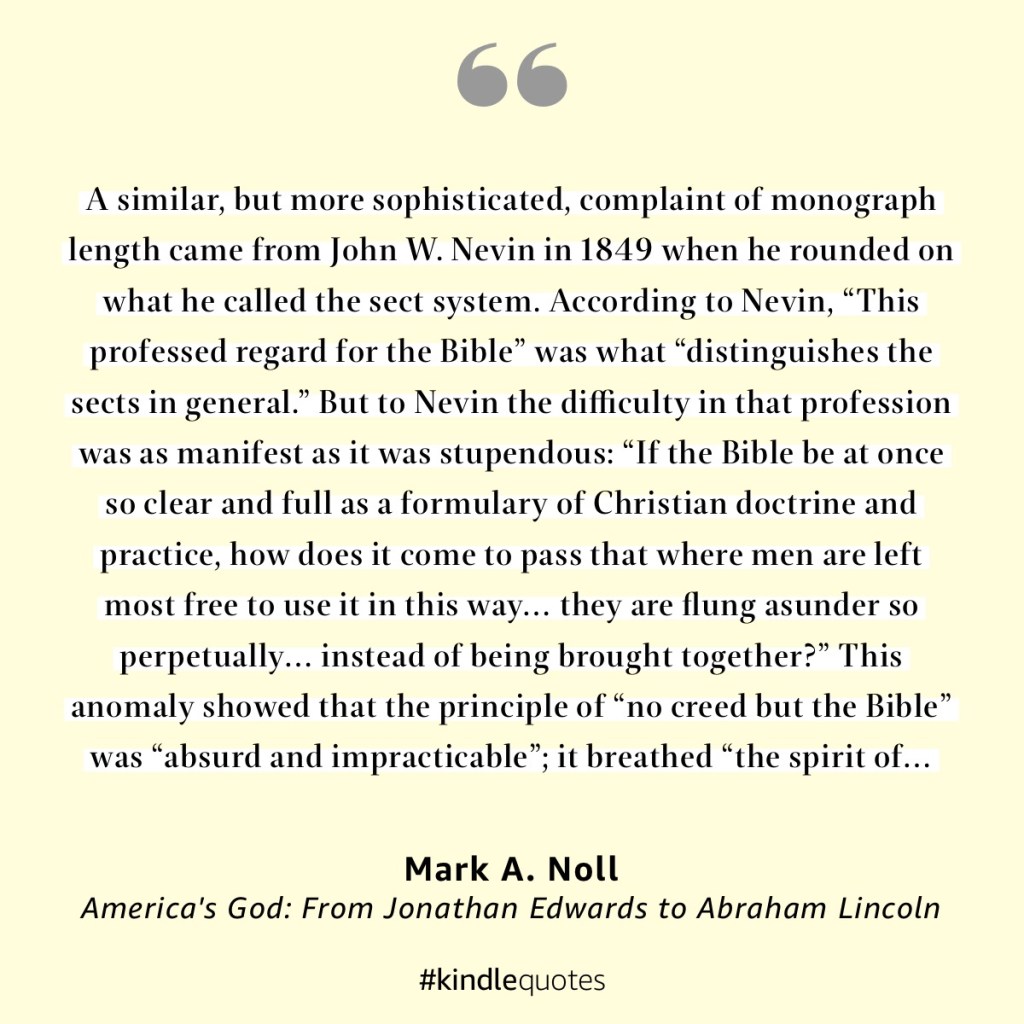

Why so much doctrine in catechesis?

Frs. Andrew and Stephen, in an un-transcribed asynchronous Q&A podcast, observed that although catechesis ideally should be more about how to live an Orthodox life, less about what the Orthodox Church believes (90% of that can be gotten from Kallistos Ware’s The Orthodox Church), nonetheless people come to Orthodoxy thinking, for instance, “St. Paul taught X, Y and Z in Romans” when in fact he did not so teach. Leaving that Protestant artifact unaddressed will lead some people to a place where they feel that the Church is contradicting St. Paul. So we’ve got to do some doctrine in catechesis.

My comment: One of the doctrines we need to emphasize with converts coming from a left-brain culture is that praxis may be more important than doctrine.

Caveat Zeitgeist

These passions are worth careful examination, particularly as they have long been married to America’s many denominational Christianities. I think it is noteworthy that one of the most prominent 19th century American inventions was Mormonism. There, we have the case of a religious inventor (Joseph Smith) literally writing America into the Scriptures and creating an alternative, specifically American, account of Christ and salvation. It was not an accident. He was, in fact, drawing on the spirit of the Age, only more blatantly and heretically. But there are many Christians whose Christianity is no less suffused with the same sentiments.

Golden Rule, misapplied

“Why do you defame us?” asks the former president. “Why concentrate on the negative? We give you the Alumnus of the Year award, and you turn around and lambaste us in your writing every chance you get.” Blindsided, I don’t reply right away. Finally, I say, “I don’t intend to demean anyone. I guess I’m still trying to sort through the mixed messages I got here.” He doesn’t back off. “I know all sorts of juicy stories about people in Christian ministry,” he says. “But I would never write about them because of the pain it would cause. I go by the Golden Rule: Do unto others as I would have them do to me.” Later, as his comment sinks in, I realize that is the very reason I probe my past, even though it may cause others pain. My brother’s question plagues me still: What is real, and what is fake? I know of no more real or honest book than the Bible, which hides none of its characters’ flaws. If I’ve distorted reality or misrepresented myself, I would hope someone would call me out.

Philip Yancey, Where the Light Fell.

Yancey’s interlocutor wants to be left alone, and thinks that’s the meaning of the “Golden Rule.” Yancey won’t leave him alone because he wouldn’t want to be left alone if he strayed.

I’m with Yancey, but it seems like the world around me, including purported Christians, is almost unanimously with his interlocutor.

A most kingly Reformation

Predictably, secular authorities convinced by the reformers’ truth claims liked the distinction drawn between the necessity of obedience to them and of disobedience to Rome. They liked hearing “the Gospel” accompanied by such “good news”—it would allow them, for starters, to appropriate for themselves all ecclesiastical property, including the many buildings and lands that belonged to religious orders, and to use it or the money from its sale in whatever ways they saw fit. In two stages during the late 1530s, seizing for himself the vast holdings of all the hundreds of English monasteries and friaries, Henry VIII would demonstrate how thoroughly a ruler could learn this lesson without even having to accept Lutheran or Reformed Protestant doctrines about grace, faith, salvation, or worship.

Brad S. Gregory, The Unintended Reformation

That God-shaped hole

“There is a God-shaped hole in every human heart, and I believe it was put there by evolution,” [Jonathan Haidt] said. He was alluding to the seventeenth-century French philosopher Blaise Pascal, who wrote extensively on the nature of faith.

“We evolved in a long period of group versus group conflict and violence, and we evolved a capacity to make a sacred circle and then bind ourselves to others in a way that creates a strong community,” Haidt told me.

Ferguson added that “you can’t organize a society on the basis of atheism.”

“It’s fine for a small group of people to say, ‘We’re atheist, we’re opting out,’ ” he said, “but, in effect, that depends on everyone else carrying on. If everyone else says, ‘We’re out,’ then you quickly descend into a maelstrom like Raskolnikov’s nightmare”—in which Rodion Raskolnikov, the protagonist of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, envisions a world consumed by nihilism and atomism tearing itself apart. “The fascinating thing about the nightmare is that it reads, to anyone who has been through the twentieth century, like a kind of prophecy.”

Peter Savodnik again.

The emergent culture

In the emergent culture, a wider range of people will have “spiritual” concerns and engage in “spiritual” pursuits. There will be more singing and more listening. People will continue to genuflect and read the Bible, which has long achieved the status of great literature; but no prophet will denounce the rich attire or stop the dancing. There will be more theater, not less, and no Puritan will denounce the stage and draw its curtains. On the contrary, I expect that modern society will mount psychodramas far more frequently than its ancestors mounted miracle plays.

Ross Douthat, Bad Religion

Religious ideas have the fate of melodies, which, once set afloat in the world, are taken up by all sorts of instruments, some woefully coarse, feeble, or out of tune, until people are in danger of crying out that the melody itself is detestable.

George Elliot, Janet’s Repentance, via Alan Jacobs

You can read most of my more impromptu stuff here and here (both of them cathartic venting, especially political) and here (the only social medium I frequent, because people there are quirky, pleasant and real). All should work in your RSS aggregator, like Feedly or Reeder, should you want to make a habit of it.