- Ears good; eyes, nose, tongue, touch bad

- Seven Protestant Sacraments?

- When is a change of affiliation a “conversion”?

- Religious education in GB

- Scholar to the Common Man

- Ideas have

consequencesantecedents - Shouldn’t that be enough?

The item is too short to excerpt, because Robin Phillips already distilled it, so I’ll shamelessly quote the whole thing:

In his book Reformed Theology and Visual Culture , William Dyrness makes some interesting observations about Calvin which echo some of the points I made in my earlier blog post ‘Are Calvinists Also Among the Gnostics? ‘ In commenting on a quote from Calvin’s Theological Treatises where the reformer noted that “it is not necessary that Christ or for that matter his word be received through the organs of the body,” Dyrness writes,No bodily organ is necessary, Calvin wants to claim, but of course some organ must be used. For apart from actual hearing (in the actual performance of worship), one could never receive the truth of the preached word with or without a believing heart. So in fact the ear is privileged over the eye (the function of which has been reduced to a cipher for comprehension). And it is the word that becomes especially joined to the work of the Holy Spirit. But one wonders: why should the ear be any less capable of mishearing or falling for obstinate superstition than the eye? Or contrariwise, if faith involves a special kind of perception, why must the Holy Spirit be joined only to the aural word of preaching and not to some parallel word made flesh (visible)? After all in the earlier history of the Church such a relationship found ample support in the biblical doctrines of creation and incarnation. One could argue of course that Calvin, along with the other reformers, is recovering an emphasis that is biblical and which results from his own careful rereading of the texts. But clearly his own reactions to medieval practices, which we have reviewed, provided an important component of the context in which he did his exegesis.

This “privileging of the ear,” in case the context is unfamiliar, involves the centrality of preaching, in Churches stripped bare of visible symbols, in Calvinistic thought.

Smell, taste and touch anyone?

Dyress’s observation seems self-evidently true, though I’d never heard it expressed before. But his was only my first theological shock on Thursday. The second came from Dale Coulter, who tells of his days as one of an international group of Pentecostals engaged in ecumenical dialog:

At one point in the conversation the Pentecostal team was asked about our views of the sacraments: Do Pentecostals believe in the sacraments and how many? One of my fellow team members immediately responded in the affirmative and said that we Pentecostals had seven. After recovering from a bit of shock at this answer, I interjected that this perspective did not hold true for most Pentecostals in the United States.

At the first break I inquired further about this view among Pentecostals in former Communist nations. Did they really hold such a view of the sacraments? Much to my surprise I was told that in lands historically Orthodox, Pentecostals had drunk deeply from Orthodox life and this affected their theological development. While it remains true that many Pentecostals still function with a Zwinglian view of the sacraments, there is a small, but growing effort by some Pentecostal theologians and church leaders to recover a more robust sacramentalism. These efforts remain part of a broader dialogue with Orthodoxy, Catholicism, and Patristic thinkers as well as an extension of the spirituality central to Pentecostal life and witness.

(Emphasis added) Wow! Pentecostals who believe in seven sacraments! Who would have thought it? And apparently there’s a growing tendency toward sacramentalism in Pentecostalism. Read the whole Coulter piece.

Rod Dreher comments on it, too.

Need we any more proof that nobody gets their religion solely from the Bible, when Pentecostals can buck the rest of Protestantism on the number of sacraments?

Is rolling in the aisle one of the seven?

I had a teensy “Aha!” moment when I mused on how it sounds to Protestants when I say I “converted” to Orthodoxy.

“Converted” is not a term I ever would have used for my friendly teen abandonment of the Evangelical Covenant Church (in which I had been raised) for a “Bible Church” near boarding school where I was baptized at age 17. I likely would not have used it (I don’t believe I did) for my hostile and decisive abandonment of a half-hearted Dispensational Premillennialism for Reformed Amillennialism in my late 20s.

Why, then, “converted” for a change to Orthodoxy, as I likely would have said had I changed to Roman Catholicism as well?

I think the answer is that my change to Orthodoxy added a significant new (for me) belief on which I thought Protestants perniciously wrong: I began to believe not only in Christ, in whom I had believed all along, but in His Church, in which I had been taught effectively to disbelieve by spiritualizing it and moving it from a visible reality to an invisible and rather gaseous antiChurch. Or as Richard John Neuhaus put it, I became an Ecclesial Christian, one for whom faith in Christ and faith in His Church is one act of faith, not two.

Perhaps no topic within Christianity generates more difficulty than the Church. I take this difficulty to be a hallmark of the accuracy of Orthodox thought in the matter. It is salt in a theological wound. The following thoughts will doubtless offer more salt – but the wound is real and cannot be imagined (re-imagined) away.

The early Church struggled for several centuries to rightly confess the God/Manhood of Christ. Expressing the reality of the Incarnation pushed the boundaries of language and gave to the world such words and concepts as “Person.” The failures of the same period also gave the world the most long-lasting schism in Christian history: the division between Oriental and Eastern Orthodoxy. In the modern period, the doctrine of the Church, or rather its absence and distortion, has given rise to a landscape populated with “churches” whose very multiplicity is an icon of human brokenness.

In the Nicene Creed we confess “One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church.” It is an article of faith no less important than any other phrase within the Creed. That the modern, visible expression of the Church so utterly contradicts this article of the Creed should be a matter of collective shame for Christians. However, the modern solution has been to hide from the shame by changing the meaning of the Creed or simply ignoring it.

(Fr. Stephen Freeman, The Politics of the Cup) When I could no longer ignore or reinterpret the Creed, that was a conversion.

Fr. Stephen continues, in a way that some would see as a shift but which he argues is integral, to the connection between Church and Eucharist, and how expectations for eucharistic “hospitality” reflect misunderstanding of the Church and the Eucharist:

An individualized, democratic culture sees the Eucharist as an entitlement and the refusal of eucharistic “hospitality” to be an insult to Christian unity. The refusal of eucharistic “hospitality” is not an insult to unity – it is rather the careful and accurate expression the boundary of the Church …

The Open Cup represents the individual’s relationship with Christ without regard for the Church. It is the unwitting sacrament of the anti-Church.

(Emphasis added)

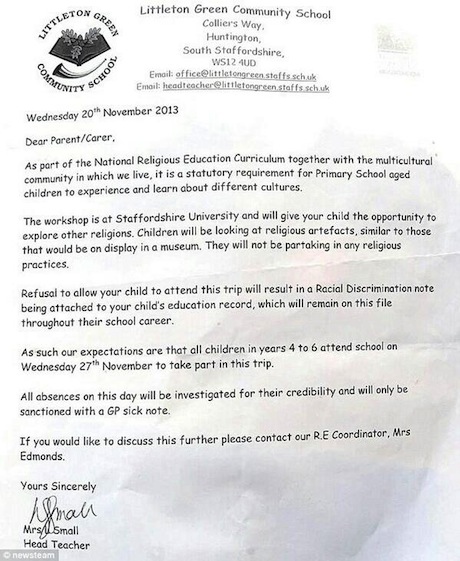

I cannot resist sharing this bit of “religious education” without commentary:

If you must have commentary, Rod Dreher provides some.

It was not always so in British education:

Because of [C.S.] Lewis, I can have interesting theological discussions with people who never went to college. I’ve met troubled college students who found solace in Mere Christianity, four-year-olds who delighted in The Magician’s Nephew, 50-year-olds who love to ruminate over The Abolition of Man. The beauty of Lewis’s legacy is that it transcends class, country, and age. Even 50 years after his passing, he continues to teach us all.

(Gracy Olmstead, C.S. Lewis: Scholar to the Common Man)

Yeah, yeah, yeah: “Ideas have consequences.” Gotcha.

Ideas also have antecedents. Practices lead to theories. The way we’re used to behaving will establish intuitions that guide our thinking.

This is (one of?) the conclusions of Mary Eberstadt, in How the West Really Lost God. Not only do family structures change when religious convictions change, but religious convictions change in symbiosis with family structure or the lack thereof. Ken Myers’ interview with her is the first substantive track on Mars Hill Audio Journal Volume 119. She specifically rejects the common atheist and modernist thought:

Well of course the Churches are empty. We’re smarter than our ancestors. We can do without god. We’re more rational, we’re more prosperous, and that’s why Christianity is diminishing.

She continues that Christianity depends on the family for its transmission. It even depends on the family to tell its own story, which after all is the story of a baby with parents who sacrified for him. It’s a story of a holy family. When a significant number are not living in families and not having children, then Christianity loses its cachet.

It’s even hard for Christians to “keep the faith” when they have family and friends whose practices are clearly outside the moral norms of Christian family. Therein lies the truth, attenuated though it be, of the charge that “you’d feel different if it were” [someone close to you].

I am writing these words shortly after yet another argument with my precocious twelve-year-old daughter about why she has to come to Mass with us, an argument that usually ends with me frustrated and her in tears. She claims that she is an atheist and hates going to Mass. Of course, she says she hates going to Mass in the same tone that she uses to say she hates showers or cleaning her room. My fourteen-year-old son is not particularly passionate on these questions, but has made clear that he has no intention of going to Mass when he is no longer under our supervision.

…

I am not worried that my children will be bad people. They are too much like their dutiful parents for that. I am sure they will be gainfully employed, take jury service seriously, and yield to drivers attempting to merge ahead of them on the highway. Both of them are kind, and sensitive to injustice, and will no doubt volunteer some of their time to help the less fortunate as they pursue their chosen careers. In that way, their lives will mirror our own.

Shouldn’t that be enough? Perhaps it should. But if one believes, as I do, that the point of Christianity is not primarily to make people well behaved but rather to proclaim what Reinhold Niebuhr once called “the nature and destiny of man,” then it seems to lack something essential. I don’t think I would do my children any favors by pretending otherwise.

(J. Peter Nixon, Now and Then, I Feel It’s Working – Part I of Raising Catholic Kids)

* * * * *

“The remarks made in this essay do not represent scholarly research. They are intended as topical stimulations for conversation among intelligent and informed people.” (Gerhart Niemeyer)